Learning Resources

How is Nottingham linked to the Trans-Atlantic enslavement economy?

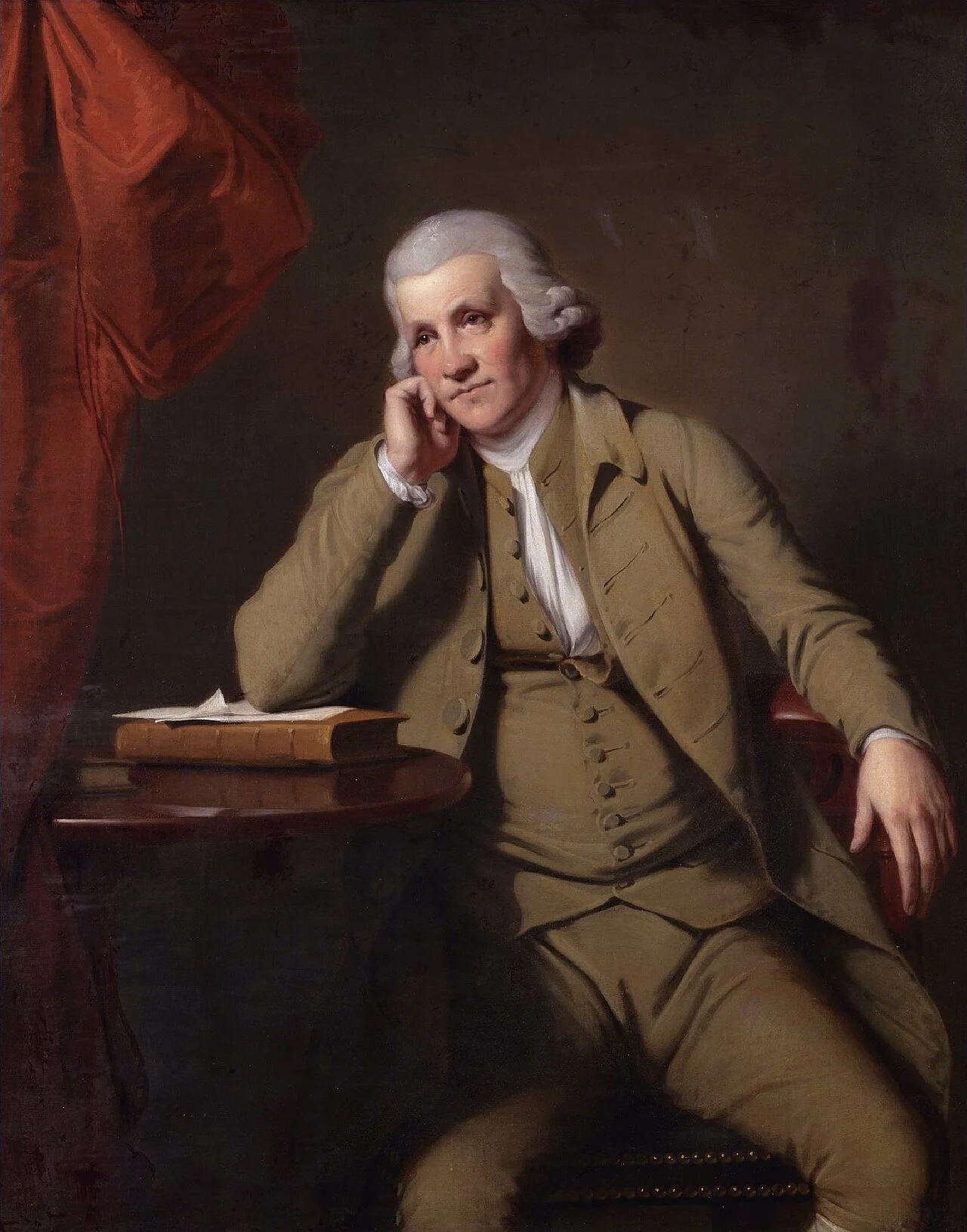

Sir Richard Arkwright: inventor of the water frame and hydro-powered cotton mills

Global Cotton Connections

The research for this timeline was conducted by Dr Susanne Seymour (Director of The Institute for the Study of Slavery, University of Nottingham), Dr Cassandra Gooptar (University of Hull), Dr Sheryllynne Haggerty, the University of Nottingham, the Arkwright Society, and Nottingham Local Studies Library - with additions from the Standing In This Place Team.

The findings demonstrate how Nottingham’s industrial expansion, made possible by individuals such as Sir Richard Arkwright and the Jedidiah Strutt family, was inseparable from the labour of enslaved Africans on plantations; as they forcibly harvested the cotton which made Nottingham's local lace and textile trade possible.

This timeline challenges the selective memory that celebrates Nottingham Lace as a local achievement, whilst omitting the violence and exploitation of British colonialism and enslavement.

It’s estimated that 9,520,548* enslaved people were transported across the Atlantic in ships to the Americas and Caribbean in the period between 1701-1866.

Cotton Timeline - Global

Cotton Timeline - East Midlands

Scroll down to find a 1862 list of women and girls of African descent, enslaved upon Spanish Wells Plantation, Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, USA, whose owner William Eddings Baynard supplied raw Sea Island cotton to the Strutts in 1823.

Spanish Wells Cotton Plantation

The Strutts and Richard Arkwright directly link Nottingham to the Trans-Atlantic Enslavement Economy through the cotton trade and industrial revolution. The Strutts imported raw Sea Island cotton from plantations worked by enslaved Africans, whilst Arkwright’s cotton-spinning innovations in the East Midlands industrialised this enslaved-produced material on a global scale - forever connecting Nottingham’s textile production and economic growth to the labour and exploitation of enslaved people overseas.

Enslaved women and girls of African descent were core workers in the cotton fields of the southern states of America, valued by enslavers for their skills in planting, weeding and picking cotton at speed.

Enslavers also regarded enslaved women of childbearing age as vital reproducers of their unpaid cotton plantation workforce.

Women and girls of African descent challenged enslavement on cotton plantations in a variety of ways, including slow working, growing and selling food to earn money, resistance to motherhood, escape, armed resistance, and building kinship ties through the making of quilts.

Source: Gooptar, C (2022) Sea Islands & Jamaica: Tracing the Enslaved People.

(Report 3 for The Scott Trust.) University of Hull, pp.12-15.

Supported by researchers at: University of Nottingham & The University of Hull

Spanish Wells’ Register of Enslaved People

The Spanish Wells plantation register documents individuals who were forcibly enslaved and may have produced cotton for the Derwent Valley mills, yet the names recorded are those assigned by enslavers rather than their original identities. This practice of renaming was a deliberate tool of domination, aimed at erasing cultural and familial connections and dehumanising enslaved people as property.

Registers such as this one offer critical evidence for understanding the psychology of enslavement, as enslaved Africans were subjected to the power of social control within enslavement plantations, and remain affected by intergenerational legacies of dispossession and identity erasure.

Scroll through the names below as we continue to acknowledge their existence and contributions.

Who were the Strutt Family of Belper?

The Strutt family of Belper, Derbyshire, were world-leading industrialists in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, instrumental in the development of cotton manufacturing in the Derwent Valley, and wider British Empire. Their legacy is closely tied to the global cotton trade, which was deeply connected to the system of enslavement.

Dr. Susanne Seymour has extensively studied the Strutt family's involvement in the cotton industry by researching how the Strutts' mills in Belper and the surrounding Derwent Valley were part of a broader network that relied on cotton produced through enslaved and indentured labour, particularly in the Southern U.S, India and Egypt; emphasising the global nature of Nottingham’s cotton trade and its reliance on exploitation. Dr. Seymour's research is part of the Global Cotton Connections project, which aims to explore and acknowledge the historical links between British cotton production and enslavement. The project has facilitated discussions and exhibitions, such as those at Cromford Mill, Masson Mill and other heritage sites, to educate the public about these connections and encourage reparative actions.

In summary, the Strutt family's industrial endeavours in the Derwent Valley were not isolated or localised to the East Midlands, as they were integrated into a global system that depended on the exploitation of enslaved peoples through their Trans-Atlantic Enslavement Economy connections with William Eddings Baynard and Hilton Head Island.

Jedediah Strutt: A hosier and cotton spinner from Belper

Stony Baynard Plantation, owned by William Eddings Baynard

Hilton Head Island Plantations

Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, was a significant site for Sea Island cotton plantations from the 18th century onwards, with 14 documented plantations. The island climate and sandy soils were ideal for cultivating the high quality cotton favoured in the Derwent Valley textile mills.

Major plantations such as the Spanish Wells and Stony Baynard Plantation, both owned by William Eddings Baynard, relied entirely on enslaved Africans for free labour to produce raw cotton that was exported to British manufacturers, including the Strutt family in Nottingham.

Life on these plantations was harsh and precarious, as enslaved women, men, and children performed intensive agricultural and domestic work under constant threat of family separation. The Hilton Head plantations were deeply integrated into the Trans-Atlantic Enslavement economy, and the wealth generated through enslaved labour directly linked enslavement in North America to Nottingham’s cotton and lace industries.

Although the Stony Baynard is nothing but ruins today, the preservation of historical sites in their true context is crucial for understanding the global histories of enslavement, trade, and the social foundations of industrial textile production - especially when Nottingham’s industrial history is concerned.

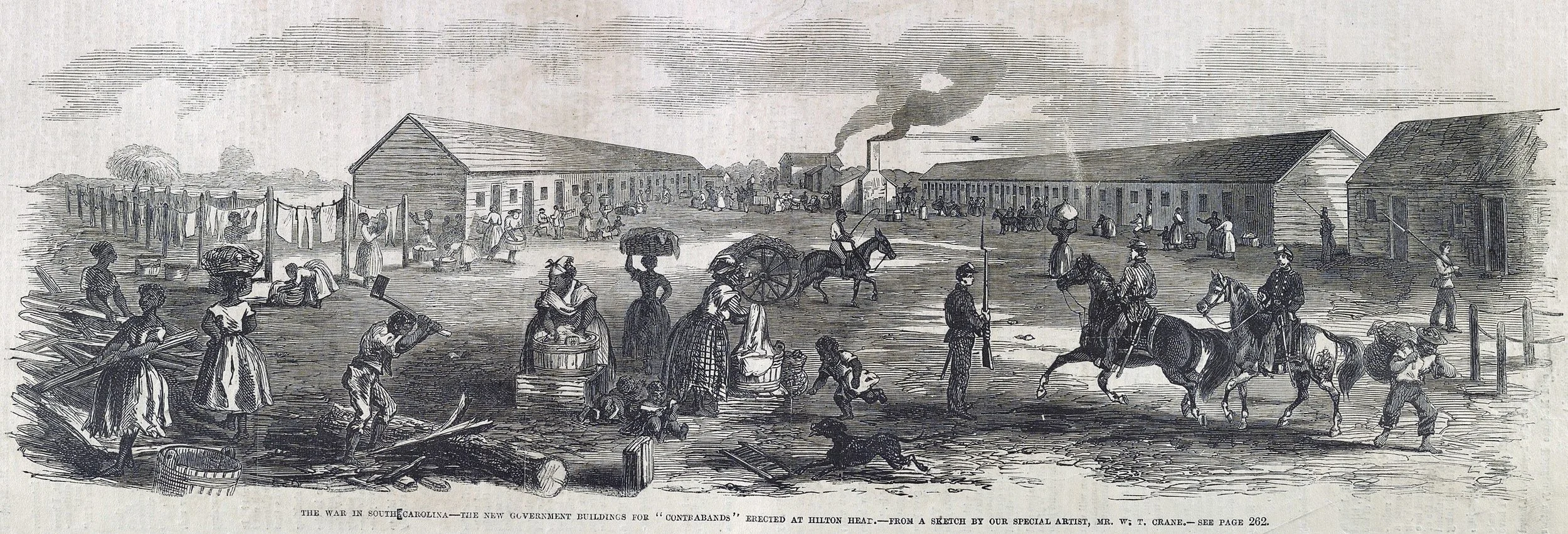

The liberation of Hilton Head Island

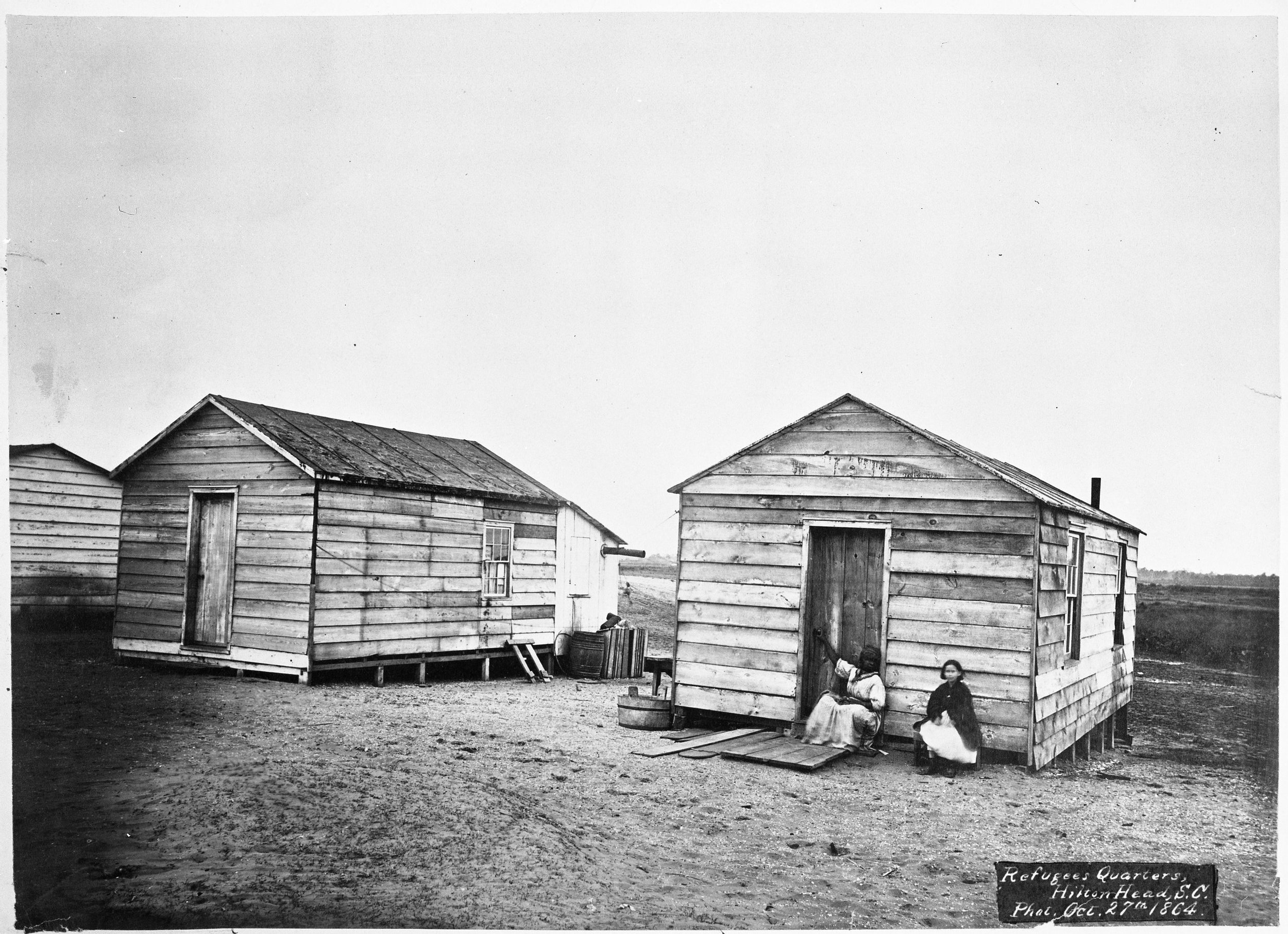

In November 1861, Union forces captured Hilton Head Island during the Civil War. This victory forced plantation owners and their families to abandon their estates, leaving behind around 10,000 enslaved Africans and African Americans.

With the enslavers gone, the island became the site of the Port Royal Experiment, a large-scale experimental effort by the Union to transition formerly enslaved people to self-sufficient freedom by creating a society with schools, hospitals, and opportunities for land and wage labour after the Civil War began. Under Union supervision, formerly enslaved people were emancipated and employed for wages on the land they once worked in bondage.

In 1862, the Union army established Mitchelville, the first self-governing town of freed people in the United States. Named after Union General Ormsby Mitchel, the town became a symbol of Black self-determination and refuge during Reconstruction by demonstrating the capacity of enslaved communities to thrive when given the opportunity.

Refugee Quarters, Hilton Head Island, 1864